A Soviet zoologist with a passion for long-extinct mammals set out to reinvigorate the landscape of the Caucuses in the 20th Century. Azerbaijan still bears the scars of his ambition today.

In the mid-20th century, Russian zoologist Nikolai Vereshchagin embarked on an ambitious expedition through the mountainous landscapes of Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia. His mission was to document the region’s lost wildlife, cataloging remnants of animals like steppe mammoths and Turanian tigers that once roamed the Caucasus. Along Azerbaijan’s Caspian coast, he found cave paintings of a once-lush savannah inhabited by aurochs, gazelles, and wild goats.

Vereshchagin’s discoveries culminated in his 1954 book, The Mammals of the Caucasus, which traced the region’s ecological evolution from natural climate change to human impact. The Soviet authorities praised his work for its unique blend of history, paleontology, and stories of local hunting traditions. However, Vereshchagin’s goal was not merely documentation—he aimed to re-engineer the region’s ecosystem by reintroducing animal species.

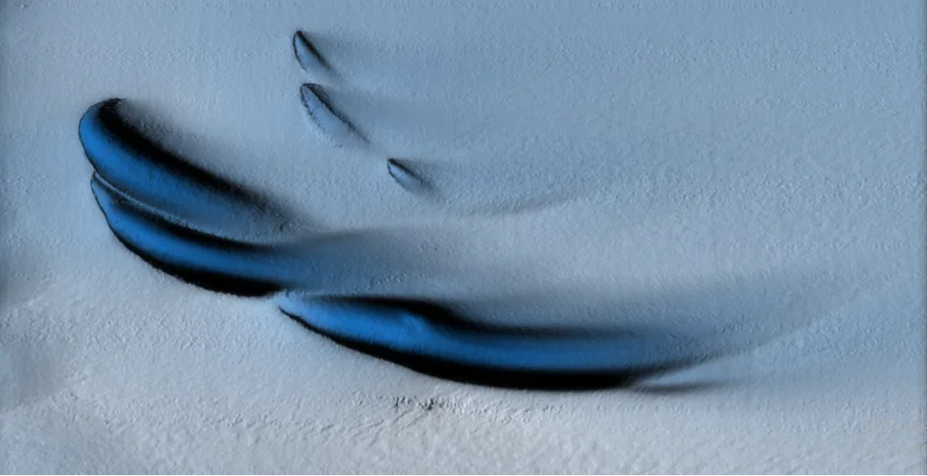

As part of a Soviet-led push to reshape natural landscapes, Vereshchagin introduced non-native species into Azerbaijan, including short-tailed chinchillas, raccoon dogs, and coypu, a South American rodent valued for its fur. Of these, the coypu thrived, spreading through Azerbaijan’s wetlands and creating ecological challenges by damaging riverbanks and outcompeting native species.

Coypu’s resilience and reproductive rate have resulted in their spread across the Caucasus, where they now disrupt ecosystems and contribute to riverbank erosion. Today, researchers like Zulfu Farajli are investigating the extent of coypu’s impact and tracking its spread. However, with little comprehensive data, the full environmental toll of Vereshchagin’s bold experiment remains uncertain.