When scientists peered beneath one of Antarctica’s floating ice shelves, they were surprised to find an upside-down landscape of peaks, valleys and plateaus.

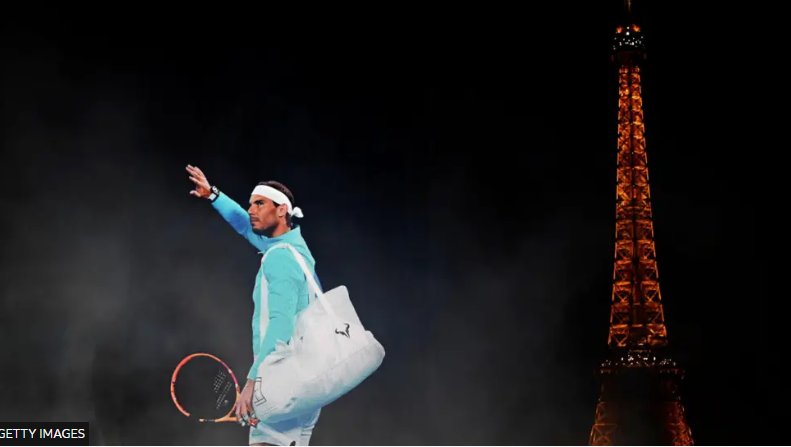

We were surprised – we had to double-check it was real,” says Anna Wåhlin, a professor of physical oceanography at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. She and her team made a startling discovery beneath Antarctica’s Dotson Ice Shelf – an extraordinary, otherworldly ice landscape.

In 2022, Wåhlin led an international group of scientists in deploying an unmanned submersible under 350 meters (1,150 feet) of Antarctic ice. For 27 days, the submersible, named “Ran,” traversed more than 1,000 kilometers (621 miles), using advanced sonar to create the first-ever map of an ice shelf’s underside. What it revealed was astonishing: peaks, valleys, and patterns resembling the swirls and scoops of a lunar surface.

“It really does look like this – there are these shapes,” says Wåhlin. “There is a landscape of ice down there we had no idea about before.”

Mapping the Unknown

The unprecedented exploration provides a clearer picture of how the ocean interacts with Antarctic ice. As meltwater flows beneath the ice shelf, it carves intricate formations, shedding light on the melting process and the potential global implications of rising sea levels.

The West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS), an ice mass the size of India, is melting at an accelerating pace. Glaciers such as Thwaites, Pine Island, and Kohler drain WAIS into the ocean, threatening to raise sea levels dramatically.

“Thwaites alone could cause global sea levels to rise by 65 centimeters [26 inches],” warns Alex Brisbourne, a glacier geophysicist at the British Antarctic Survey.

Although ice shelves like Dotson float and do not directly contribute to sea level rise, their melting destabilizes the glaciers they buttress, allowing land-based ice to flow into the ocean.

A Technological Triumph

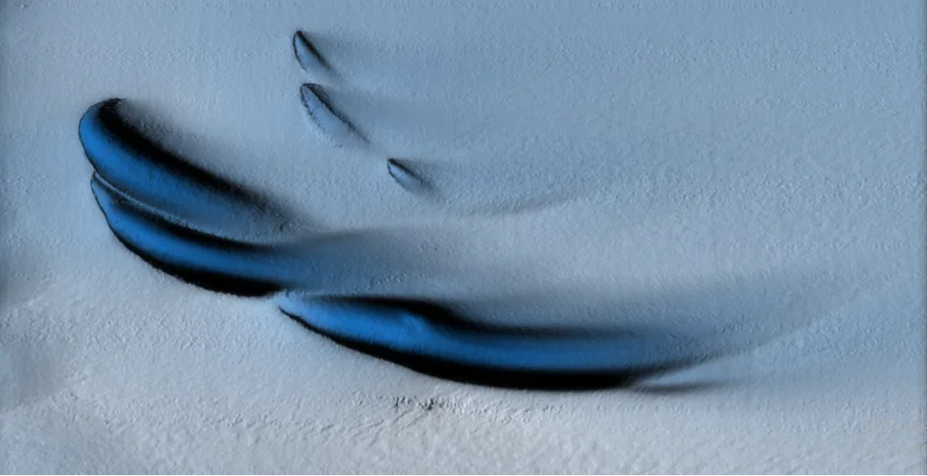

Accessing the ice shelf was no small feat. Icebergs and sea ice blocked the team’s path to the Thwaites Ice Shelf, redirecting their research to Dotson. Despite the challenges, the submersible Ran returned with detailed images of the underside, revealing fascinating contrasts:

- Eastern Section: Thick, slow-melting ice with Grand Canyon-like plateaus and swirly patterns.

- Western Section: Thin ice with smooth surfaces, fast currents, and scooped-out formations – some teardrop-shaped and up to 300 meters (984 feet) long.

“It looked like a giant had taken an ice cream scoop and carved into the ice,” describes Wåhlin.

The study also revealed vertical fractures throughout the ice shelf, further emphasizing the dynamic and complex nature of Antarctic ice.

The Bigger Picture

As scientists work to understand how warm ocean water accelerates ice melt, the stakes couldn’t be higher. At COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, world leaders discussed the dire consequences of rising sea levels, while 16,000 kilometers (9,904 miles) away, research teams like Wåhlin’s were gathering critical data to inform the conversation.

The findings from Antarctica underscore the urgent need to predict and mitigate the impacts of climate change. Understanding the secrets of the ice not only reveals a hidden world but also offers crucial insights for the future of our planet.